Quit Talking About Revenue and Start Talking About Profit

If you've ever compared notes with someone in the construction industry about the size of your respective companies, inevitably you start with top line revenue. Everyone does it. It makes sense because revenue is the easiest way to get a ballpark of the scale of a business. If I told you that general contractor A does $10M in annual revenue while general contractor B does $1B in annual revenue, its pretty obvious which one is bigger.

The problem with revenue is that it doesn't tell you anything about the health of the business. A healthy company is one that generates PROFITS. Yes, revenue is a critical component towards generating profits because profit is what is left over from revenue after subtracting costs. But if that $10M GC is generating $1M in profit, and the $1B GC is losing $10M, which one is healthier?

In my career, I've met midsize contractors who are wildly profitable where the owners take home as much as the top brass of the big companies, employees get great bonuses, and staff retention leads the industry. I've also seen big, splashy companies that have signs everywhere but who barely breakeven year to year. (Note that the reverse is also true: there are small and midsize companies who don't make money, and big companies that make gobs of cash. The size as measured by revenue isn't what's important!)

Measuring Companies by Profitability

We've established that revenue isn't a good metric - so what is? How do you measure the relative profitability between companies?

Whenever the conversation shifts to profit, the most common number I hear thrown around is percentage fee or margin - ie, how much of each dollar of revenue turns into profit. Percentage fee is a flawed metric, however, because it assumes that every dollar of revenue is of the same quality.

For general contractors, we have jobs that are more challenging compared to others, and the level of difficulty has a major impact on our ability to turn revenue dollars into profit dollars. Imagine two projects - a large, greenfield warehouse project that is mostly just concrete, steel, simple cladding, and basic M&E systems vs. the fit-up of operating theatres inside of an active acute care hospital. I guarantee that it requires much more effort from the GC team to earn the dollar of revenue at the hospital than the dollar of revenue at the warehouse.

As a result, the warehouse project should have a lower percentage margin than the hospital project. Does that in itself make the hospital a better project? Not necessarily. The hospital project will take longer to generate the same amount of revenue (and therefore profit), and likely requires more project management and field supervision than the warehouse.

The best way to think about profits is to normalize difficulty (the amount of management and supervision required), schedule (how long it takes to generate revenue), and margin (how much revenue turns into profit) to allow us to compare the relative health and value of projects or companies. The metric that makes the most sense for measuring the profitability of a general contracting firm is:

Relative Profit = Margin per person per month

Where margin is measured in absolute dollars, and people is the number full time equivalent project management staff + field management staff.

A project that makes more money for each human resource in a given month is more profitable than a one that makes less.

It's worth noting that margin (the amount of profit we generate from our installed work) and markup (the amount that we add on top of costs during estimating) aren't the same thing. When talking about profits, we need to focus on margins. Markups don't mean anything until the work is done and the dust has settled. Determining what your markup should be in order to hit your margin is a whole other topic for discussion.

Staff Tenure as a Proxy

Great mathematical equation, Andrew, but nobody shares their profit numbers publicly. So while it might be useful for internal comparison purposes between projects, how can we compare across companies where the profit numbers aren't known?

Companies that employees consider to be "good" tend to also be the ones that are profitable. Good companies provide staff with higher compensation packages, training programs, and better work opportunities - all of which cost money. Good companies use their profitability to provide work conditions that encourage their staff to stick around which means that staff tenure can be used as a proxy for profitability.

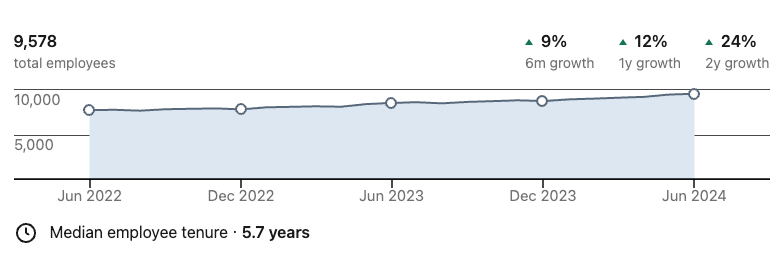

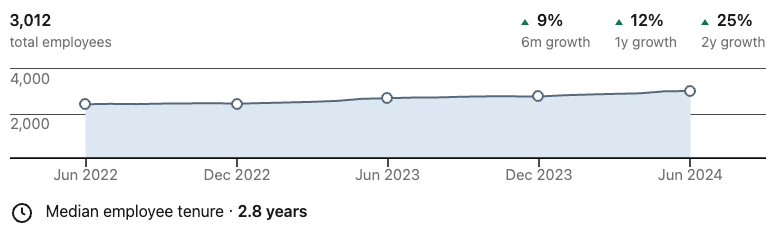

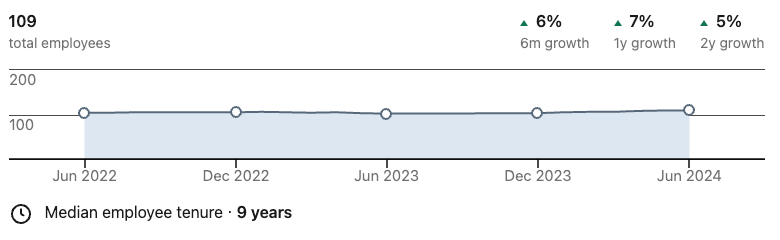

Here are four companies - two large and two midsize - who operate in similar markets and have all been in business for a long time... grow rates in headcount are similar, but note the differences in tenure.

I would be willing to bet that the companies with the longer tenured staff are also more profitable.

Thanks for taking the time to read this. If you would like receive regular nuggets of wisdom like this one delivered to your inbox, please join the community as a subscriber!

This article, and all other articles published on this site represent my personal opinions and are protected by copyright laws. Andrew Langstone is a construction industry leader and founder of the construction marketing software, Pursuit Zen.